|

|

Oleona

Base: The Secret Post Office at Stonington Island

About Stonington

Island

The

Preservation of East Base

EAST BASE - THEN AND NOW

Narration of a Slide Lecture

Edith M. "Jackie" Ronne

On the Second Byrd Expedition in

1934, Richard Black and Finn Ronne conceived the idea for additional

American exploration in the Antarctic as they rested on top of Mt. Nielson

on their return from a long sledge trip. Later, through the intervention

of Alaska's Governor Gruening with President Roosevelt, these small plans

snowballed into the United States Antarctic Service Expedition of

1939-41. A half million dollars was appropriated by Congress to explore

new territory and do scientific research at two bases.

From a map dating to the late 1930’s,

it was clear that there was much geographical information missing in the

Peninsula area. With the southern tip of South America to the right and

the Antarctic Peninsula left of it near the center, there are only dotted

lines hinting at unknown coastlines and features.

West Base was set up near the former

Little America site on the Ross Ice Shelf in east Antarctica with Paul

Siple in charge. East Base was established on Stonington Island in West

Antarctica in March 1940 with Dick Black in charge. Although Admiral

Richard Byrd had been named Commanding Officer, he did not remain in the

Antarctic during their year of operation but instead returned to his home

in Boston. Both bases were under the administration of the Department of

the Interior.

Aerial flights helped them in finding

a suitable location. It ended up on a rocky island (in the middle of the

photo – part of the ice ramp) named Stonington, after Stonington,

Connecticut, the hometown of Nathanial Palmer who discovered Palmer

Peninsula. It was located near mountainous Neny Island in Marguarite Bay.

This island was chosen because a

snowy ramp led up to the long sloping glacier giving the necessary access

to the six thousand foot high plateau dividing the Antarctic Peninsula

north and south to the mainland.

All prefabricated building walls were

carried down on the decks of the North Star.

Finn Ronne was named Second in

Command and was the engineer in charge of setting up the prefabricated

double wooden paneled well insulated buildings with doors resembling the

commercial refrigerator type.

It was an early use of prefabricated

construction and it tested inovative building methods and materials. The

base consisted of a large bunkhouse, with five two man cubicles set

against the outer wall on either side, a good size galley with coal

burning range at the end of the building and two long mess tables placed

end to end occupying the center aisle. There was also a science building

complete with meteorological tower, on the right, here; a machine shop; a

storage shed; and various other outpost buildings.

During the winter night the

twenty-six men made plans and preparations for exploratory plane flights

south in their Curtis-Wright Condor biplane and for surveying sledge

parties by dog teams into the unknown. When the weather and surface

conditions were good, it was wonderfully exhilarating to be out in the

field enjoying the magnificent scenery, but very often a grueling job and

under blizzard conditions there was nothing more miserable and monotonous.

One party headed south in the Weddell

Sea area, while Finn Ronne of Norwegian background and his very good

friend Carl Eklund of Swedish descent, headed southwest to make one of the

longest, fastest and most successful dog team trips on record. With the

support of two additional dog team parties on the first part of their

journey to establish food caches for their return, they traveled 1,264

miles in 84 days of surveying.

Sun sights were taken twice daily in

order to get an astronomical fix and establish their accurate position.

They proved what Sir Hubert Wilkins had suspected, that King George Sixth

Land was instead an island off the Mainland which thus eliminated any

possibility that the Russian Expedition under Von Bellingshausen had first

sighted the continent there in 1821.

At their furthest south location,

they built a cairn and placed claim sheets in the snowy tower. It was

believed that in the touchy area of claiming, if necessary, these claims

would establish U.S. sovereignty over this area.

Exploratory flights were also

conducted from the Main Base west to King George Sound and as far south as

Mount Tricorn and Cape Eielson near the Weddell Sea Coast.

In addition a scientific program was

conducted at the Main Base. By now the barkentine Bear, which was

assigned to pick up East Base personnel, made more urgent by the ongoing

war in Europe, had managed to break through the ice pack as far as

Mikkelsen Island, where solid ice surrounding Stonington Island made it

impossible to relieve the men as planned.

East Base was finally evacuated by

two very hazardous plane flights, allowing the 26 men to take only their

scientific records and a few personal items. As I recall, 98% of USAS

personnel joined the armed Services in World War II. Their work was

published in the Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society

publication in April 1945.

As World War II drew to a close, Finn

once again began making plans for his own expedition. After great

dedication and unbelievable persistence he became only the third and last

American ever to launch a private scientific expedition to the Antarctic.

The Port of Beaumont was what we

named a former ocean going tug, which was obtained on loan from the Navy

by an act of Congress. The 183 foot long wooden hulled ship was named for

our port of departure, Beaumont, Texas. Some financing came from

donations and a small contract with the Office of Naval Research for the

scientific results. Through the great interest of General Curtis LeMay of

the Air Force three small planes, one of which was equipped with

trimetrogon cameras, two weasels, and considerable amount of clothing was

acquired for testing under cold climatic conditions. A contract with the

North American Newspaper Alliance for news reports and some private funds,

mainly from friends, rounded out a minimum sum necessary for departure.

For the most part members of the expedition were volunteers.

Having assisted him in editorial

work, I was very familiar with all of his plans. It had been my intention

to handle the domestic side of the expedition from our home in Washington,

D.C. where I was employed by the Department of State and had taken a

two-week leave of absence to see him off.

Because of some last minute

unforeseen delays, Finn asked me to continue as far as Panama to catch up

with some final problems. I asked Jennie Darlington, who was recently

married to Harry, one of our pilots, and still on her honeymoon to

accompany me. We could fly back from Panama together I reasoned. As usual

I took over Finn's writing duties and before long he began to insist that

I would be of more help to him by going the entire way. This I resisted

strongly for many good reasons until the very last minute in Valparaiso,

Chile when I finally gave in. He agreed that Jennie could go with me.

The approach to the Continent through

light pack ice was magnificent. I was totally in awe of where I was going

and I anticipated a great adventure. We anchored outside a small British

Base, one of several established secretly on the Antarctic Peninsula

during the war years. When I stepped ashore with Finn, it was brought to

my attention that I was the first American woman to set foot on the

continent. I honestly had not even considered that.

The occasion was that I accompanied

Finn ashore to call on the British Leader, K.S. Pierce-Butler, who

diplomatically pointed out to us that we were on British claimed

territory. Finn replied that we were merely an American expedition

reoccupying an American-built base. After that political do-si-do, we

became great pals.

Ken Butler accompanied us over the

small hill separating the two camps to show us what had taken place. He

told Finn that within the last couple of days a Chilean ship had been in

and their personnel had been given unlimited shore leave. Unfortunately,

he was unable to control their actions at the American Base and there had

been a great deal of looting taking place. Just six years after the USAS

had evacuated East Base, it was in unbelievably disastrous condition.

After inspecting the Base, Finn had

our ship brought around into the back bay near the base so that our men

could see their new home for the next year. They started unloading the

ship and moving supplies to shore using makeshift rafts. After several

weeks of intensive fix-up, the camp was put in livable order and all hands

were able to move ashore.

The dogs were the first ashore. I

developed a good relationship with the puppy born on the way down. He was

named Kasco, after a sponsoring dog food company. Finn did not

train the dogs for this expedition as he had for the last two expeditions

he was on. He maintained a friendlier relationship with these

dogs.

Before the winternight, a trail party

established a weather station on 6,000-foot high plateau. Ignoring Finn’s

safety guidelines, the two men returning from the plateau removed their

skis in a highly crevassed area.

One man broke through an ice bridge

and fell over 120 feet head first. Finn organized a rescue party, but

with the man stuck head down in a crevasse for 12 hours, Finn expected to

find a body. Instead, with ropes they plucked him from his would-be tomb

like a tooth from a socket; with only minor injuries, the man lived to

tell the tale .

The ship was purposely frozen-in for

the long winter months in the back bay between Stonington Island and the

mainland. It was not long before the sun began to disappear on the

northern horizon and the winternight was upon us for two and a half months

of darkness. During this period intensive plans were made for the summer

field programs.

Finn and I stayed in our 12 foot

square hut, connected to the main bunkhouse by a canvas hallway that soon

became a buried snow tunnel. I wrote newspaper releases for the North

American Newspaper Alliance and the New York Times, while Finn plotted

plane flights and dog team routes for the sledge parties to follow in the

field when the sun returned.

Necessary activities in the course of

the day became a real challenge, causing you to think twice as to whether

you really wanted to make the trip there. In storms, there was a rope

tied between the main bunkhouse and the outhouse, and during blizzards you

sometimes had to hold on for dear life.

Trail gear was assembled by those

going on sledge trips. From the radio shack, we sent twice daily weather

reports to the weather bureau in Washington, as well as seismological data

from our two seismographs receiving information on Antarctic earthquakes

and microseisms for the first time. In the blubber shack dog food was

made by rendering seal blubber down to seal oil and mixed with commercial

dog food.

Parachutes were checked and placed in

the planes for each person flying. We checked out the weasels and

classes were given in navigation and safety on the trail.

On moon lit nights we skied on the

ramp leading to the high glacier overlooking our base. Well,

sometimes, we skied!

During the winternight, much drifting

snow accumulated against the buildings, burying them until Spring.

As soon as the sun returned the dogs were exercised and dog team parties

assembled. Geologist Dr. Robert L. Nichols and his assistant Bob Dodson

started off with their two dog teams on what turned out to be a 154 day

sledge trip, 54 days of which were spent completely on geological field

work, more than any geologist up to that time.

The trimetrogon equipped Beechcraft,

our largest plane, was kept on board the ship until the bay ice was strong

enough to hold its being pulled ashore by the tractor weasel. As soon as

its wings were assembled They were ready to fly. This is a view of the

planes as they were parked right adjacent to our buildings. The

Beechcraft took off on our strong bay ice runway for numerous exploratory

flights

We used the leap frog methods on the

longest ones. Our main geographical objective was to capture the last

unknown coastline in the world, that 500 mile stretch from Palmer Land to

Coats Land, which established the fact there could be no frozen strait

dividing the continent between the Ross and Weddell seas at that point.

There was even open water at the head

of the Weddell Sea. On the second long exploratory flight, they followed

the Mountainous Palmer Land Plateau to where it dies out in higher land

continuing south.

Every available flying day was spent

doing exploratory trimetrogon flights. Camera mounted in the fuselage of

the plane were focused on each horizon and straight down, taking

simultaneous photographs with 60% overlap. Altogether, they flew 39,000

miles in 346 hours in the air, almost twice as much as any expedition thus

far. 86 landings were made in the field, more than half of which were

unsupported. 14,000 aerial photographs were obtained supported by ground

control points obtained by surface parties, so that accurate maps could

be made over this part of the Antarctic by the aeronautical chart service

of the Air Force. The red lines show the flight tracks and the entire

area inside the bubble lines was mapped. 250,000 square miles of

new territory, or the size of Texas was discovered and the very first

landing ever was made on Charcot Island.

Prior to leaving on the expedition,

Finn had been secretly sworn-in as a 4th class U.S. Post Master

and he established the first U.S. post office in Antarctica, naming it

Oleona Base. I took this photo of a quick display of the sign, as he and

I were the only ones who knew of its existence. He cancelled opening date

and closing date covers that were later given to the State Department and

the Post Office Department for assisting in possible future land claims.

The Antarctic Treaty of 1959 – 61 holds all national claims in abeyance.

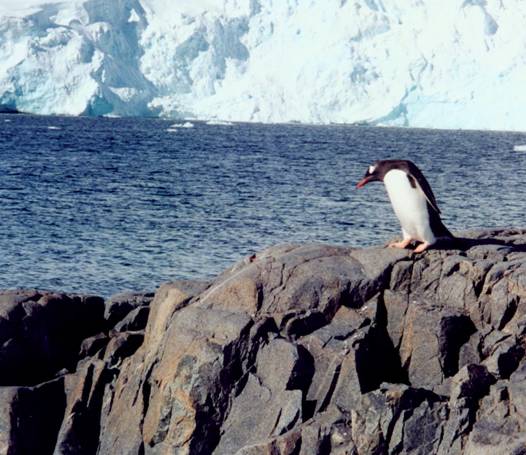

Meanwhile, at Base, shown here from

the glacier, investigations continued in climatology, terrestrial

magnetism, seismology, geology, and other branches of science. Of course,

the study of penguins is always a popular branch of science. Fourteen

scientific reports were published by the Office of Naval Research upon our

return.

All of our plans had been carried out

very successfully. It was time to go - our flag was lowered, our ship

reloaded and led to open water by a visiting American icebreaker. Our

thoughts turned northward wondering if we would ever see Antarctica

again. Some of us did.

Waving enthusiastically to crowds who

gathered, we were glad to sail by the Statue of Liberty as we were

greeted by a celebratory water spray. Upon our arrival in New York, we

were well received by the American Geographical Society.

Back at East Base, after RARE left,

subsequent expeditions of various nationalities removed everything from

the interior of the buildings. The British dismantled the Machine shop

and probably used the wood to put in the second floor in the Main

Bunkhouse that covered ice accumulated from a broken skylight and used the

higher space to store dead seals for dogfood. They used the Science

building for sled repair and rope storage. Interior walls were removed -

only a short section remains.

In 1989 East Base was designated a

historic monument under the Antarctic Treaty. The National Science

Foundation has assumed preservation of the buildings, artifacts and

surroundings as an important reminder of the early days of American

exploration of the continent. In early 1991, two National Park Service

archeologists were sent down to assess the material remains of

archeological and historical value at East Base.

Another visit was made to East Base

by the National Science Foundation in 1992 to clean up potentially

hazardous materials and unsightly trash areas. They also made necessary

repairs, patching open walls and roofs. They installed protective and

educational signs.

In 1995, my daughter and I made an

unexpected visit to the Base on the tourist ship "Explorer". Although not

publicized as such, their priority seems to have been to get me ashore at

East Base after an absence of nearly forty-eight years.

Although I had since returned to

Antarctica twice, including a trip directly to the South Pole in 1971, I

never thought it would be possible to return to this uniquely special site

and certainly not with my daughter, Karen, to be able to share it with

her.

By piling two large rocks on top of

one another, we were able to peer into the Ronne Hut, as it was now

labeled, and saw the empty room used by the British in the 1950s for an

emergency generator on concrete pad in the center of the floor. Gone

were the numerous shelves for personal belongs, the tables holding my

typewriter and Finn’s desk, our double bunk, the small coal burning stove

which kept us warm, curtains on the two windows Finn had made to give us

views of the surrounding grandeur, and the canvass wall coverings that

provided interior decoration. Now, it was bare and barren.

The same was true of the large

bunkhouse - there was nothing left of the bunks, tables, chairs, galley

stove and kitchen equipment - nothing, nothing, except frozen snow in the

rear which the NSF personnel had chipped away, but not completely

removed. The Science building faired a bit better exhibiting a small wire

caged museum containing bits and pieces of crockery and other very small

things picked up around the buildings to show visitors these buildings had

once housed two good sized American expeditions bent on exploration and

scientific research.

My daughter, an architect, had made

three large plaques covered with heavy plastic, which we screwed tightly

into the wall. One gave the history and accomplishments of the Ronne

Expedition, another gave Finn’s biography and the third was about my

participation in the expedition and my life, to date.

After taking some photographs and a

last look, we returned to the ship in silence. I was grateful to have

seen East Base once again, and I hope many more travelers will experience

a visit to the remnants of the oldest remaining U.S. presence in

Antarctica.

About Stonington Island:

55 Buildings and artefacts on Stonington Island, Marguerite

Bay, Antarctic Peninsula. 68°11'S, 67°00'W. Buildings and

artefacts at and near East Base of the US Antarctic Service

Expedition, 1940-41, and the Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition,

1947-48.

East Base, Stonington Island (68° 11'S67° 00'W). Buildings and

artifacts and their immediate environs. These structures were erected

and used during two U.S. wintering expeditions: the Antarctic Service

Expedition (1939-1941) and the Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition

(1947-1948).The historic area is 1000 meters in the north-south

direction (from the beach to Northeast Glacier adjacent to Back Bay)

and 500 meters in the east-west direction.

The size of the historic area is approximately 1,000 meters in the north-south direction

(from the beach to Northeast Glacier adjacent to

Back Bay) and approximately 500 metres in the

Reclaiming a Lost Antarctic Base. By Michael Parfit, Photographs

by Robb Kendrick. In National Geographic Vol 183, No 3, pp

110-126, March 1993. A survey and restoration team visits "...historic

East Base, the United States' first permanent toehold in Antarctica,

surrendered to the cold in 1948." East Base was established in 1940 on

Stonington Island, Marguerite Bay, Antarctic Peninsula. It was here

where the first two women winter-overed: Edith "Jackie" Ronne and

Jennie Darlington.

The Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition (1947-48),

led by Finn Ronne, was the last privately sponsored U.S. expedition.

Using Byrd's old base on Stonington Island, Ronne closed the

unexplored gap at the head of the Weddell Sea.

The first woman to set foot on the continent was Caroline Mikkelsen

from Norway. She landed at Vestfold Hills on February 20, 1935, with

her husband who was a whaler. The first women to winter in Antarctica

were Edith Ronne and Jennie Darlington in 1947. They spent a year with

their husbands on Stonington Island in the Antarctic Peninsula region

during the Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition (American naval

commander Finn Ronne led this expedition which discovered the Ronne

Ice Shelf at the southern coast of the Weddell Sea). The first women

to see the South Pole were two stewardesses aboard a commercial flight

that flew over the Pole as it traveled from Christchurch to McMurdo in

1957.

Captain Finn Ronne, USNR/Military Commander Scientific

Leader/Ellsworth Station, Edith Ronne Land/Antarctica".

Norwegian-born Finn Ronne came to America in 1923 when he was 24. He

was with Byrd in Antarctica (1933-1935, 1939-1941) and led

his own Antarctic expeditions in 1946-1948, 1958-1959 and

1962-1969. Ronne was the Commander of the Weddell Sea Station

during the International Geophysical Year (1956-1958). The Ronne Ice

Shelf is named in his honor.

CRM at East Base, Antarctica

The ice-breaker slowed to the pace of a row boat as it crunched

through the brackish ice of

the LeMaire Straits. Disturbed crab eater seals looked briefly toward

the big red boat, then slid

away into the sea. Penguins, startled in disbelief at the intruder,

dove off their ice blocks. We

were bound for Stonington Island, site of America's and Antarctica's

most recently designated

historic monument. Captain Alex of Erebus ensured our safe arrival on

February 21, 1991,

the final destination of a journey that began six months earlier with

a phone call.

Much of the environmental community is disturbed about the untidy

nature of the

continent, and the National Science Foundation, concerned as well, had

initiated measures to

clean up former research stations.

While planning their effort, they recognized the historic significance

of "East Base,

Stonington Island," site of an early winter-over expedition. Further

research and conferences

changed the NSF mission from clean-up to one of sympathetic

preservation of the site while

ensuring that hazardous materials were removed. After a 1990 field

check, they found that

East Base, the oldest remaining U.S. base in the Antarctic, had a host

of artifacts. That is

when they called the National Park Service for technical advice. In

February, we boarded a

boat bound for Antarctica.

East Base was established as part of Admiral Byrd's third expedition

to the Antarctic

(1939-1941). Known officially as the U.S. Antarctic Service Expedition

(USASE), the full

scale exploration of the continent was supported by President

Roosevelt. Admiral Byrd

established two bases, West Base at Little America III and East Base

on Stonington Island.

The base was a cluster of U.S. Army, knock-down buildings built by a

crew of 23 under

Richard Black. The men used a Curtiss-Wright Condor airplane and dog

sleds to survey the

peninsula. In 1941, as wartime pressure increased and the pack-ice in

the bay prevented a

planned departure by ship, Black decided to hurriedly evacuate the

base by air. Crates of food,

a spare plane engine, a tank and tractor and much gear were left

behind. In 1947-1948, the

privately funded Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition (RARE)

re-occupied East Base. Finn

Ronne, Richard Black's second in command, led RARE and conducted more

explorations.

The RARE expedition was also significant for being the first site

where women (Edith

"Jackie" Ronne and Jennie Darlingon) wintered-over in the Antarctic.

When we arrived, on a calm, sunny (55 degrees) uncommon Antarctic day,

the

completeness of the site amazed us. Buildings and material culture

were in surprisingly good

shape. Pothunters and bottle collectors would have destroyed a similar

50-year-old site in the

United States. Trash dumps contained material in incredible condition-a

1939 Reader's

Digest in which one could read about sex education in public schools,

a shirt from Ike

Musselman, one of the USASE crew, bottles from the doctor's office, a

spare 1930s Curtiss-

Wright plane engine, hay piles, and three of the buildings. Everything

had a history, a history

pieced together by published books, records at the National Archives

and interviews. Mrs.

Jackie Ronne drew us a layout of her hut on a napkin at a MacDonald's

restaurant in

Washington, DC before we left. It helped piece together on-the-ground

evidence: stacks of

trail mixings, caches of coal for stoves, and on and on.

Our report, a description of resources and recommendations for

management, will be used

by the National Science Foundation to manage the site and, in the

immediate future, remove

any hazardous material: a corbel of acid from the science lab,

sulfuric acid from the doctor's

office and other dangers. The team will repair and make air-tight the

buildings, unfortunately

much altered on the interiors by a nearby British base. The former

bunk house was used as a

seal-slaughter house and is befouled with the waste. Preservation

crews will patch the

building and lock it shut. Its fate is uncertain. The valuable

artifacts in the trash dumps will not

be salvaged at this time. At present a light covering of gravel from

the island will serve as a

cap to ensure their preservation, allowing future archeologists to

excavate the site based on our

field mapping and photographs, as well as improve the present

unsightly appearance of the

As the preservation and clean-up effort is underway, the National

Science Foundation will

prepare interpretive signs to ensure that the East Base Historic

Monument is not impacted by

increased visitation. The site, as a listed Antarctic national

monument, may become a

destination point for the few tourist boats that venture south along

the scenic Antarctic

Peninsula. The number of visitors to the site are few, but during our

journey we met

Australian, French and British tourists, the former while we were at

East Base.

As the movement for a world park on Antarctica continues to be

discussed and introduced

in Congress, we need to continue to stress the importance of people in

the Antarctic story. The

East Base site is but one piece of the whole century and a half of

exploration and discovery.

The site deserves preservation. Cultural resource management will

continue to be an important

part of the management of Antarctica.

Cathy Spude is an archeologist with the Western Team at the Denver

Service Center,

National Park Service. Robert Spude is chief, National Preservation

Programs Branch, Rocky

Mountain Region, National Park Service.

Oleona Base: The

Secret Post Office at Stonington Island

Oleona Base

Cover - the "Holy Grail" of Antarctic Philatelic Covers

A Secret

U.S. Post Office operated in Antarctica 1946-1948

causing speculation about the real reason behind two concurrent U.S.

expeditions...

Finn Ronne

Finn

Ronne was a Norwegian immigrant who later joined the United States

Navy and was a member and officer in Admiral Byrd's earlier

expeditions to Antarctica. In 1946-8, he led a privately-financed

expedition to Antarctica, following upon the heels of Operation Highjump.

Ronne's expedition was to the Marguerite Bay area, where he reoccupied

Byrd's 1939 Base. One of the most important results of this expedition

was a showing that the Antarctic peninsula was connected to the rest of

Antarctica, thus solving one of the last great public mysteries of the

continent.

Writing in his book

entitled "Antarctic Conquest", he stated:

"Although no one knew

it, I had been operating a United States Post office too, but

for reasons of state

(emphasis added) had been

compelled to keep it secret."

Secrecy seems to be in no

scarcity as it relates to several Antarctic expeditions; perhaps in no

small way due to a continued concern that the Nazis had a remnant left

in Antarctica from their infamous 1938-9 "New Schwabenland" colonization

of Antarctica. Note carefully the Swastika in the following photo of

aircraft aboard the Schwabenland, the vessel that took them south.

(Photo source unknown, and is

presumed to be in the public domain)

The web is abundant with sites setting forth information about suspected

and actual German involvement in Antarctica possibly dating back even to

the late 1800's. It does make one wonder if there were in fact,

covert or as they say today, "black-ops" reasons for one or more of the

Byrd Expeditions (including Operation Highjump for this discussion) as

well as the private expedition of Captain Ronne.

Many online sources are available with information concerning what I

have dubbed the "Byrd Conspiracy", which was not a conspiracy by

Admiral Byrd, rather what may have been an apparent conspiracy by the

government to keep particular information that he had uncovered during

Operation Highjump as a secret. I am not passing judgment at this time,

as I am still investigating the whole thing to my satisfaction.

However, lending credence to this conspiracy theory is the observation

that Admiral Byrd does in effect seem to "disappear" from public view

shortly after his return from Operation Highjump in 1947-- until

approximately 1955 when he organized Operation Deep Freeze I, and he

was reported to have been hospitalized (in a mental ward) shortly after

his return in 1947. This forced hospitalization is said to have came

upon the tails of Byrd having made some remarkably candid comments

(which included what smacked of being a description of a UFO) to

a South American newspaper about what he had found during Operation

Highjump. His disappearance from the scene after his arrival back in

the states, would make it appear he may have been promptly

squelched! Remember that this time period coincided roughly with the

Roswell UFO sightings. Operation Highjump would have been first, early

in 1947, and then Roswell to follow in the summer of 1947. This was a

situation that was the last thing the government would have wanted,

another military official (in this case a quite prominent and popular

man who had spent years criss-crossing the United States giving lectures

and whose word would have been quite respected and accepted) who

apparently reported having seen/and or believing in UFOs!!

NOTE: If Op HJ had continued to its full expected duration of

six to eight months, they would have still been in Antarctica at the

time of Roswell. The expedition headed back to the U.S. in early 1947,

well short of its expected ending. Some would say "limped back", after

suffering great losses of personnel and equipment. The official record

only sets forth a limited loss of life and aircraft, but conspiracists

feel the record has been doctored or we are not being told the full

story.

Contrast this lack of

public accessibility after Operation Highjump, to the

previous well-known availability of Admiral Byrd in the period following

his first two Antarctic Expeditions, where there are documented

philatelic items from cities all over the country serving as

commemorations of where Byrd visited lecturing to the public about his

travels in Antarctica. That Byrd loved to travel and lecture about his

polar explorations is quite evident.

The polar regions and his

expeditions were his very reason for existence; he had said from the

time he was a child that he felt destined to be a polar explorer. He

had a passion for all things polar, especially exploration, that could

scarcely be contained. Operation Highjump was at least

as important in many respects, it would appear, as his previous

expeditions... so where was he after his return? Where did he go? Was

he locked away so he couldn't share the story of what he really had

found in Antarctica? As some theorists suggest, during Operation

Highjump, did he encounter and engage Nazi forces operating from bases

that lodged advanced aircraft with advanced propulsion systems?

Many think so, and I am beginning to see some curiosities about many

aspects of Operation Highjump and now, perhaps even with Ronne's

Expedition.

The little tidbit mentioned above that

Ronne forked us in his book, only begins to tell us why the

Oleana Base, Antarctica postmark is one of the rarest polar cancels that

exist. With this being the first American post office established on

the Antarctic continent, it is a shame that the cancel was not used more

often. Is there perhaps a larger reason why this post office was kept

secret? We do know that many countries, including Britain, had

concurrent secret bases and or expeditions in the same general time

period, notably Port Lockroy on the Antarctic peninsula. Port Lockroy

was part of a top secret World War II British expedition called

Operation Tabarin.

Operation Tabarin was the beginning of Britain's permanent

presence on the Antarctic continent, and was built to serve as a

southern outpost and to keep an eye on suspected Nazi presence on the

ice. In a 2001 BBC interview, one of the last remaining survivors of

that secret expedition, Gwion Davies, noted that the posting of mail

from their secret base was a way of their laying claim to, or

establishing that section of Antarctica as British sovereign territory.

In other words, just as the Nazis are known to have dropped metal dart/

markers with the Third Reich swastika emblem over a large area of

Antarctica during their expedition in 1939, to act as a laying of a

claim; for any country (such as Britain) to have a post office that

actually accepted and postmarked mail definitely shows an intention on

their part of not only establishing a base, but of staying.

While the United States did not then, and does not now, recognize any

country as having specific territorial claims upon Antarctica, for Ronne

to have allowed his expedition members to have open mailing of letters

from Oleana Base would have served a similar purpose as with Port

Lockroy, but for some reason, he would not allow that to be done. Why?

Some mail did escape, and other mail from members of the Ronne

Expedition is known to have been posted from nearby British bases. The

posting of mail often serves a geo-political purpose in addition to the

simple fact it carries mail back home to loved ones; and it is a great

curiosity to many polar philatelists and followers of Antarctic history

that it was not done in this instance. The full story about the

existence of the post office (as well as even greater secrets?) may have

passed with Captain Ronne.

The "Holy Grail" of

Antarctic Covers

Click on the above image

for a larger view; copy of cover was provided courtesy of Scott Smith

The Oleana Bay

covers are most commonly seen with a date of March 12, 1947, which was

the date the expedition arrived at Marguerite Bay, Antarctica. In this

instance, the cover illustrated above is extraordinary in that it is on

a printed envelope from the Byrd II Antarctic Expedition,

postmarked with the less common hand cancellation from that mission;

then repostmarked at Oleana Base in 1947, with the addition of Captain

Ronne's "corner card" and the IGY Ellsworth Station octagonal cachet,

and the best part of all, Ronne's signature in which he adds the word

"Postmaster", rounding it out to make a splendid cover! A cover like

this would fare extremely well in a polar auction. I would go so far

to term it as the "Holy Grail" of a polar collection; only very few

covers I can think of would be more collectable, in my opinion.

Return to author's Main Polar

Philately Page

Wilderness of ice felt like a visit to

another planet

ANTARCTICA - When I was a

young boy, one of my parent's closest friends was Finn Ronne, one of the

world's great polar explorers. During those years, Finn often came to our

house for dinner and talked at length about his latest adventures to

Antarctica, which he affectionately described as "the last unspoiled place

on Earth."

By

dog sled, ski and ship, Finn covered more of Antarctica than any other

explorer. For hours on end, my brother and I sat at the dinner table,

mesmerized by his tales.

As

I grew older, I often recalled Finn's exploits and hoped that one day I

might also have an opportunity to visit Antarctica. But while the notion

of travelling to "the last continent" seemed pretty remote a few decades

ago, much has changed as the number of organized tours to this remote part

of the world has increased dramatically.

After reading about one such trip being organized by Australian-based

Peregrine Adventures that also coincided with the 60th anniversary of

Finn's most famous expedition, I finally decided to go.

Our

journey would commence from Ushuaia, Argentina, located on the southern

tip of South America. A city with a stunning mountainous backdrop and a

population of 45,000, Ushuaia proudly promotes itself as being at the end

of the world ("fin del mundo" in Spanish) and is often cited as the

southernmost city on the planet. It was here that I joined the other

passengers who had signed up for our expedition.

After taking a day to explore the town as well as nearby Tierra del Fuego

National Park, we finally boarded the Akademik Ioffe, a relatively small

and manoeuvrable expedition ship that would be our home for the next 11

days. Late that afternoon, we set sail into the Beagle Channel and began

our journey to the Antarctic Peninsula.

But

first, we would have to cross the 1,000-km Drake Passage, a notoriously

violent stretch of water that separates Antarctica from the rest of the

world and, for the next two days, the passage lived up to its reputation.

The seas were big and the conditions were rough, but tolerable (thanks

largely to the Gravol we were all encouraged to bring).

During our time at sea, I read as much as I could about Antarctica. By any

measure, it's a land of extremes, being the coldest, driest and windiest

continent on Earth. To the surprise of many, it's also the highest, with

an average elevation of 2,300 metres, much of that ice.

Late on the second day of our journey, I took a walk on deck and could

feel and see a sudden change; the air was cooler and fresher, there were

several visible icebergs and a growing number of birds were circling the

boat.

We

were approaching the Peninsula!

Within hours, I saw the South Shetland Islands, our first glimpse of land.

I felt the adrenaline rush through me and, throughout the ship, there was

a sense of excitement and anticipation. We had made it and were now ready

to embark on an unforgettable journey to the most remote place on Earth.

For

the next several days, we cruised among the islands and into the bays of

the Antarctic Peninsula. On the ship, we also had a fleet of kayaks and

motorized Zodiac rafts that would enable us to explore seldom seen places

while also venturing ashore for numerous walks and hikes. And whatever

one's expectations are of such a trip, I soon realized that nothing quite

prepares you for the amazing landscapes and wildlife displays that are

found here.

We

visited many incredible places, including Deception Island, an ancient

volcanic caldera from which Nathaniel Palmer, a seal trader and explorer,

first spotted the Antarctic mainland back in 1820. The island is home to

more than 100,000 pairs of chinstrap penguins as well as a century-old

abandoned whaling station that was fascinating to explore.

Our

first foray on to the continent itself was at the beautifully situated

Neko Harbour. After landing by raft, we hiked up a steep icy trail to the

top of a hill where we enjoyed some breath-taking panoramic views of the

rugged coastline and interior mountains before deciding to slide back down

to the bottom (laughing like kids as we went!).

To

the surprise of many, the weather was downright balmy by Antarctic

standards, although it cooled quickly whenever the wind came up. We were

there right in the midst of the brief, but beautiful, austral summer and

the temperature hovered close to zero degrees Celsius for much of our

trip. By contrast, winter temperatures on the continent have been recorded

as low as minus 89 degrees Celsius.

On

Cuverville Island, we came across a large colony of nesting gentoo

penguins and, after seeing how docile and accepting they were in our

presence, I appreciated the efforts of our able and energetic expedition

leader, Hayley Shephard, in ensuring that no passenger approached the

birds too closely.

On

other days, we took our rafts through a maze of icebergs, many of which

were a dazzling blue, due to the way sunlight is reflected by the ancient

high-density ice. On these same outings, we had some amazing close-up

encounters with humpback whales as well as leopard and crabeater seals.

On

one of these occasions, two whales emerged right beside our raft, their

mouths wide open as they gorged on a swarm of krill we had drifted

through. Close enough to touch, the whales slowly sank back into the

depths of the sea, our rafts bouncing in their wake. It was a magical

moment and all of us sat there in awe.

Later in the trip, we also had a very informative visit to the Vernadsky

Research Station, currently operated by the Ukrainian government. This

facility has accumulated more than 50 years of meteorological data, which

has been invaluable to scientists working on issues such as climate change

and atmospheric ozone levels.

During our tour of the station, I asked about the anticipated impacts that

might be associated with global warming. We were told that, while it

appears that Antarctica has not yet been affected to the same degree as

the Arctic, researchers have documented a warming trend of 1 to 1.5

degrees Celsius per decade in the western Antarctic, a region of lower

elevations and more moderate temperatures compared to the eastern part of

the continent. Consequently, the glaciers and ice sheets along the western

edge of Antarctica appear to be the most vulnerable if global warming

continues unabated.

Each passing day seemed to bring something new and, while we had so many

memorable experiences, perhaps the highlight of the trip was the night

that I camped ashore. Our trip was one of the few that actually allows

passengers the option of camping -- so I jumped at the chance.

That evening in my bivy sack (a small one-person tent), I felt like I was

finally alone with the spectacular solitude of Antarctica, although it was

never really silent. The rifle-like sound of cracking glaciers, an

occasional gusty wind and the mournful braying of nearby penguins

continued through the night. Yet, it was a wonderful sound and, more so

than ever, I understood the great allure of this far corner of the planet.

Early next morning, our raft picked us up and we headed back to the ship

for breakfast. We would soon be leaving, heading back across the passage

toward Cape Horn and then on to Ushuaia.

I

started to reflect on the past several days and I felt so fortunate to

have seen a place of such incredible beauty. The trip had been a

once-in-a-lifetime experience and there is simply nowhere else on Earth

that is so removed from the day-to-day lives that most of us lead.

I

then recalled those long-ago dinner conversations with Finn Ronne when he

tried to describe to a young boy what Antarctica was like. He used terms

such as "otherworldly" and "like being on another planet" while more

recent adventurers, such as Jon Krakauer, have likened a trip to

Antarctica as a bit like going to the moon.

Now

that I've seen this crystalline wilderness, I think that's a pretty apt

description. And while I may never witness the beauty of a distant planet

or star, I knew this trip was as close as I would ever come.

We

then entered the rough seas of the Drake Passage and started the long

journey home.

-------------------------------------------

Mark Angelo is

the head of the BCIT Fish and Wildlife Department and recently received a

special United Nations Stewardship award for his international

conservation and education work.

IF

YOU GO ...

The

best (and only) time to visit Antarctica is from December to March. The

best departure point is Ushuaia, located at the southern tip of Argentina

and about a four-hour flight from Buenos Aires.

No

visa is required for Canadian visitors to Argentina. While a range of

Antarctic tours and ship sizes are available, boats of moderate size with

a fleet of Zodiacs make it possible to access a greater number of islands

and bays. Mid-sized ships also enable passengers to hop ashore more

quickly. For more information on Antarctica expeditions, contact Mountain

Travel Sobek at 1-888-687-6235 (www.mtsobek.com), Peregrine Adventures (www.peregrineadventures.com)

or Trek Escapes in Vancouver at 604-734-1066.

|